RCH150 and the RCH Archives and Collections will collaborate for a special edition of the Hospital Heroes Gallery, Clinical Excellence.

From September 2020 to February 2021 the Hospital Heroes Gallery will uncover extraordinary archival content of the people who have enabled the hospital to achieve clinical excellence since 1870.

The hospital’s rich 150 year history is defined by the commitment of staff and our community of supporters to the care of sick children. The Clinical Excellence gallery will take a step back in time, shining a light on the stories of those who helped pave the way to a brighter future for paediatric healthcare.

Proudly supported by BankVic, the member owned bank for health workers. Find out more at www.bankvic.org.au

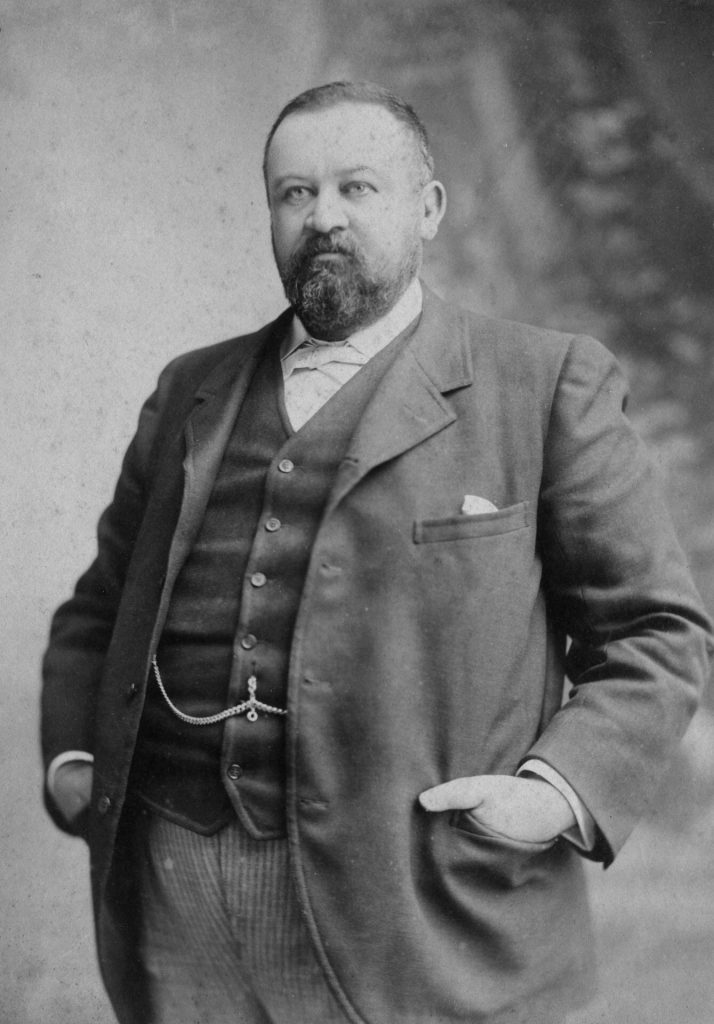

Dr William Snowball

1889, Paediatrician.

Dr William Snowball was a spokesman and strong leader for The Royal Children’s Hospital since the late 1800’s, often regarded as the founding father of Australian paediatrics. Dr Snowball represented the Honorary Medical Staff, advocated for hospital growth and was pivotal during the early stages of the hospital’s development in achieving clinical excellence.

In 1878, Dr Snowball was appointed the position of resident doctor at The Children’s Hospital – this was the beginning of his long involvement with, and influential contributions to, the hospital and its efforts.

During his tenure, he introduced strict hospital regulations around hygiene in response to the severe challenges of the diphtheria and typhoid epidemics. It was suggested during the time the Infectious Diseases Pavilion be burnt along with all of the straw beds to control the rapid contagion of patients and nurses, instead Dr Snowball introduced strict disinfection procedures and hygiene standards elevating the health standards of the hospital. Snowball approached paediatric health challenges, such as diphtheria, with education, development and growth at the centre of everything he did.

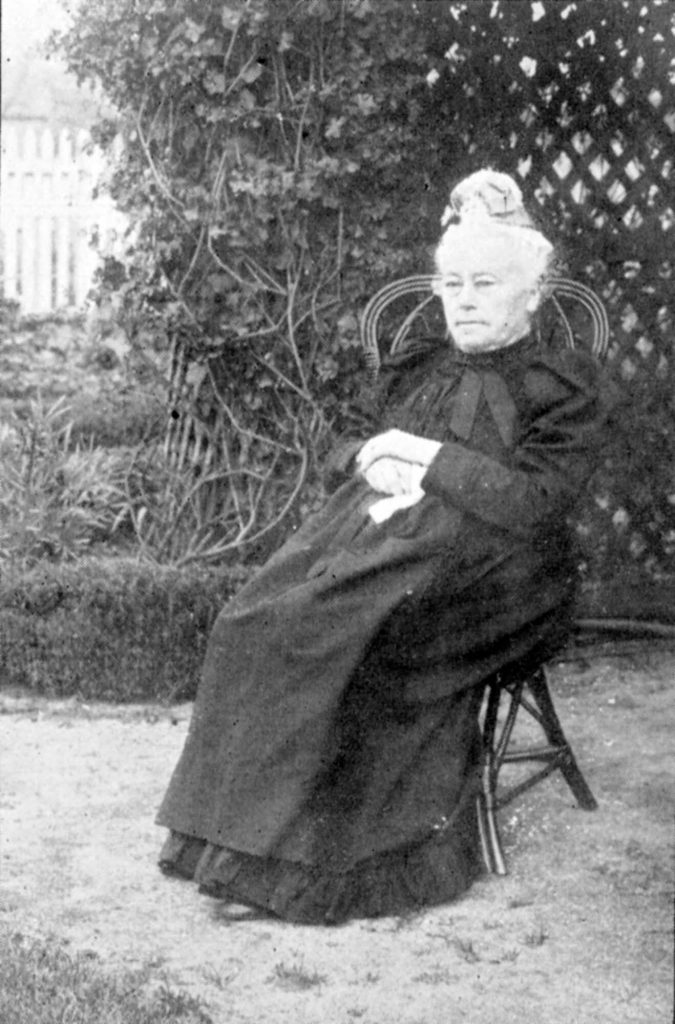

Elizabeth Testar

1878, Committee President.

Mrs Elizabeth Testar was an exception to the general rule that members of the committee were of the elite belonging to wealthy families prominent in society. Different from her peers, Mrs Testar was married to an accountant, and had no formal training or family wealth of her own. Despite this, Mrs Testar joined the hospital committee in 1871.

Shortly after her engagement, Mrs Testar was voted vice president and achieved remarkable excellence in her newly appointed position. Mrs Testar led many deputations to government ministers as well as led the development of the new hospital. It was reported she had a particular interest in architecture and drawing amazingly reducing the hospital architect’s role to a `mere draftsman’. In 1885, from her strong leadership and gusto, she was elected president of the committee, completing the expansion and redevelopment of the hospital and specialist services. A remarkable achievement for a working class woman of that era.

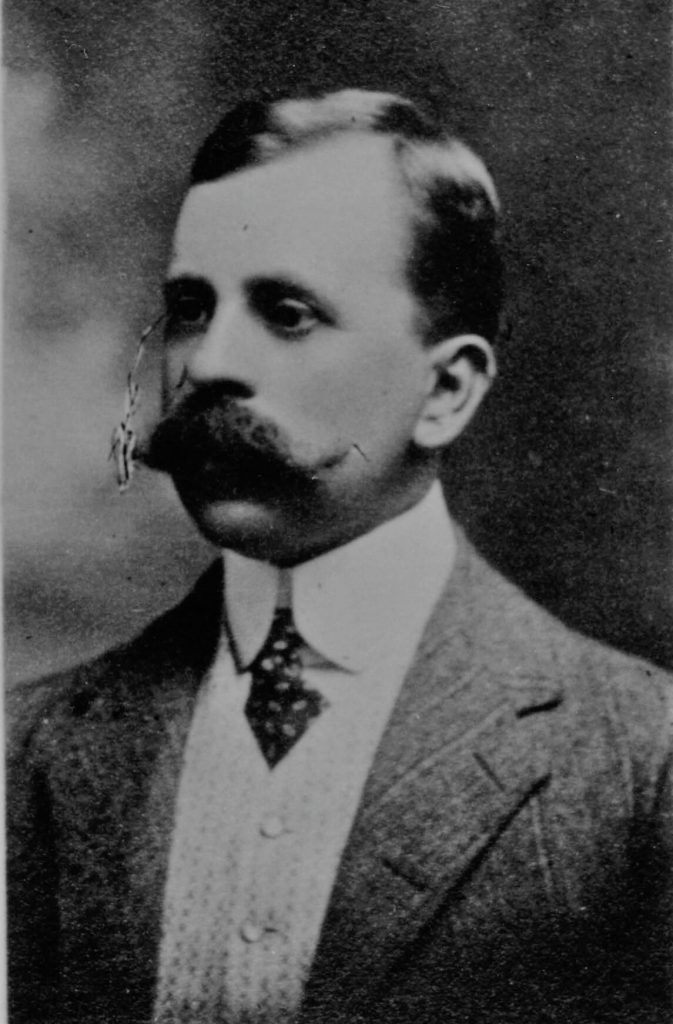

Dr Herbet Hewlett

1896, The First Radiologist.

In 1896 The Children’s Hospital became the first public hospital in Melbourne to establish a radiology department under Dr Herbet Hewlett’s leadership. Radiology and X-ray equipment were extremely new technologies, only being discovered in November 1885. The committee were thrilled to purchase the first ever X-ray equipment for £25, in which Dr Hewlett, developed as honorary skiagraphist abreast with international advances. Dr Hewlett provided revelatory research and development in what is now known as a dangerous radioactive environment. Archives documented Hewlett’s commentary:

“There were no means of testing the penetration, and for years I would put my hand in front of the platino-cyanide of barium screen in order to judge the character of the ray. If it were too soft we had to reverse the current and if it was too hard reduce the vacuum by heating the tube with a spirit lamp. Our exposures at that time for a hand would be from three to four minutes. For a spring or kidney I have frequently given an exposure of half an hour.”

Dr Hewlett’s enthusiastic leadership saw radiology developed rapidly at the hospital. Hewlett served the hospital for 37 years and retired at the age of 81, achieving extensive clinical excellence throughout his tenure.

Dr Ethel Mary Vaughan Cowan

1898, First Female Doctor at the Children’s Hospital.

Dr Mary Cowan achieved clinical excellence as the first female doctor at The Children’s Hospital. In 1898 Dr Cowan impressed the committee at a trial, enough to appoint her the clinical residency in outpatients for one month without salary. Dr Cowan continued to impress the committee, successfully obtaining an 18 month residency with the hospital ahead of four competing male doctors.

She was the first woman ever to do so, paving the way for her female successors such as Dr Constance Ellis. Dr Cowan was a clinical hero that set a precedent for women doctors and their importance in the medical workforce.

Dr Arthur Jeffery Woods

1908, Pioneer Paediatrician in Infant Mortality.

Dr Jeffery Woods was revolutionary for infant mortality rates, extending the hospital’s clinical care to neonatal children under the age of two.

Dr Woods was concerned with the exceptionally high infant mortality rates of that era, identifying summer diarrhoea caused by bad milk as the primary cause of death. Dr Wood commented in an interview, “the absolute feeling of helplessness that besets my colleagues and myself at The Children’s Hospital during the summer months, when we have 1000 babies a week coming up for treatment for diarrhoea. Medicine and advice are useless when the baby has to be sent back to the sweltering dusty lanes in the city, to be re-poisoned by dirty milk.”

Dr Woods campaigned tirelessly for accessible clean and healthy milk for babies. Dr Woods was responsible for the establishment of the baby health centre movement from 1917, ensuring the hospital would care for babies under the age of two, leading to the establishment of the babies ward in 1922, a major clinical milestone for The Children’s Hospital.

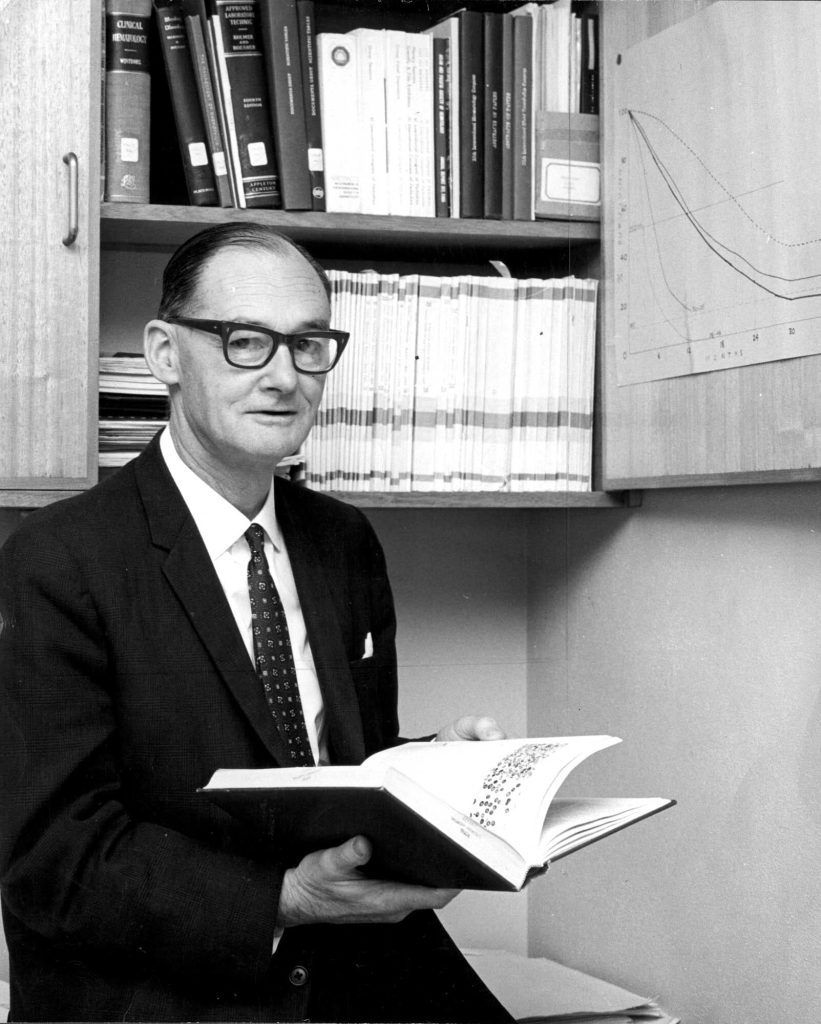

Dr Reginald Webster

1913, First Pathologist and Bacteriologist.

Dr Reginald Webster was the first full time pathologist in Melbourne, pioneering the hospital’s first laboratory which was widely regarded as the best in the state. Known for being a character of interest, Dr Webster was experimental and forward thinking in his approach to research.

During his tenure in the laboratory he achieved clinical excellence through numerous research breakthroughs. Dr Webster published important discoveries in pneumonia, the classification of endemic strains of dysentery bacilli as well as cerebro-spinal meningitis and poliomyelitis, bringing the hospital to the forefront of research and pathology.

Dame Jean Macnamara DBE

1928, Physiotherapy Pioneer.

Dame Jean Macnamara was a pivotal hero of the hospital. She was an influential pioneer of the physiotherapy department where she played a central role in developing many of the ancillary services.

Macnamara was challenged by the experimental perception of physiotherapy and worked tirelessly to ensure the practice was taken seriously. She was known for being very generous with her time and money, with much of her private practice work being unpaid. Dame Jean’s daughter recalled some parents paid for their children’s treatment with cow manure.

Despite this, Dame Macnamara was determined and wholeheartedly motivated by the health of her patients. She achieved great success in bringing a more holistic practice to those suffering from the crippling impacts of polio and cerebral palsy. Macnamara established a highly successful school at the hospital where high needs children could receive holistic treatment and education as opposed to being subject to the clinical and repressive treatment of bedrest, massage and stints.

Dr Elizabeth Turner MBBS, MD, FRACP, LLD (Hons)

1944 First Female Medical Superintendent

(Pictured left).

Dr Elizabeth Turner was appointed to the role of medical superintendent in 1944, being the first female to do so at the hospital. Dr Turner achieved extraordinary outcomes during a period of astonishing stress on the hospital as medical staff served with armed forces. Dr Turner recalls one sombre week in which there were no surgeons available at all. Despite this, Dr Turner managed to prevail, tying a meningeal artery, resecting a gangrenous bowel and removing several appendicitis. Dr Turner additionally pioneered the clinical use of penicillin, monitoring the first ever use of penicillin on a civilian Alan Goats, as well as helped to develop the traveling incubator for babies.

Dr Charlotte Anderson AM, FRACP, FRACP, FACP, FRCPCH

1946, Prominent Clinician and Researcher.

Dr Charlotte Anderson, like many of her female counterparts, was encouraged by her family not to study medicine and to pursue a domestic role within the home, however Dr Anderson defied their wishes, studied hard and obtained not only top grades but a science scholarship, enabling her to complete her studies as a biochemist. Dr Anderson completed a plethora of research for the hospital, particularly around disorders largely unknown in a clinical context. This research included cystic fibrosis, mal-absorption problems and coeliac disease. A true hero who defied the status quo to improve the lives of sick children.

Dr John Colebatch AO

1948, Pioneered Chemotherapy.

In 1935 Dr John Colebatch joined The Children’s Hospital to help develop the chemotherapy ward in line with international developments and standards. Dr Colebatch lead the hospital in cancer research and training that enabled the hospital to provide paediatric cancer treatments for the first time in public healthcare. Dr Colebatch commenced at the hospital during a time where staffing and resources were extremely thin due to health and military deployment in World War Two.

In Dr Colebatch’s first three weeks on the job, a child with scarlet fever coughed in his face, resulting in both the child and the doctor ending up in Fairfield Infectious Disease Hospital. Despite these challenges, Dr Colebatch was able to establish and build the chemotherapy unit to world class standards. As a result of his hard work and dedication, The Children’s Hospital has been recognised for its treatment for prevalent childhood cancers such as leukemia, achieving clinical excellence in supporting numerous patients with the disease.

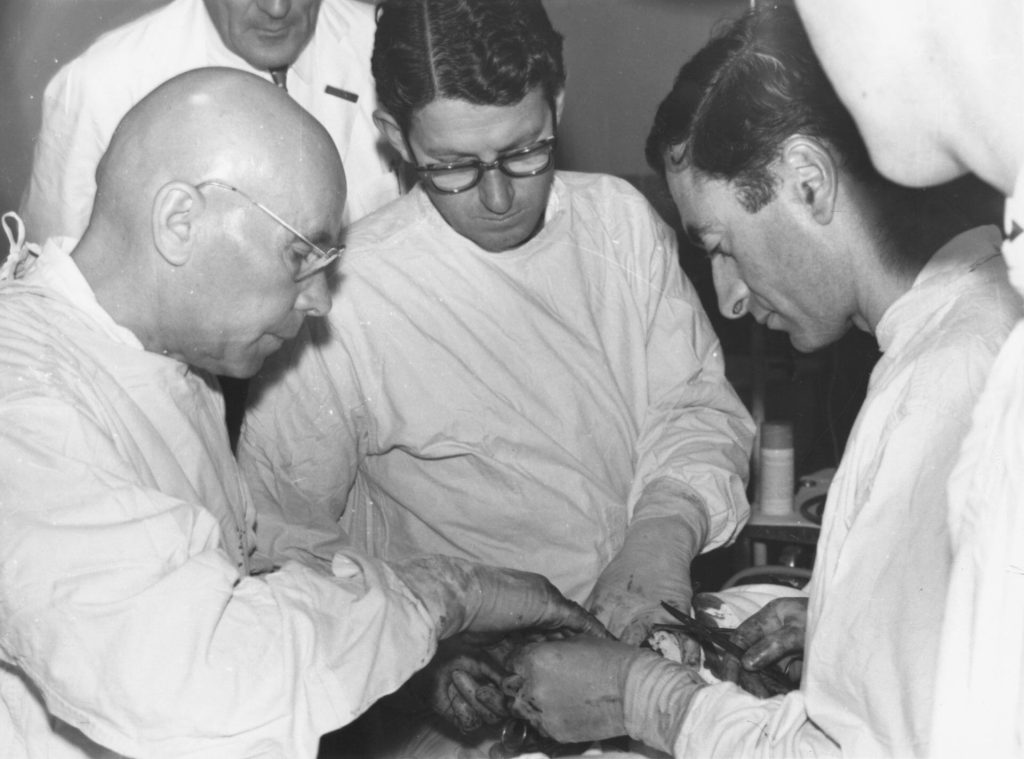

George Westlake

1959, First Paediatric Cardiac Surgeon.

A hero who faced many difficult surgeries through a time when cardiac surgery was high risk, novel and experimental with high mortality rates. Westlake persevered through many dispiriting and challenging operations, helping to develop the paediatric sector for cardiac surgeries. He achieved much success in his career, including the first successful paediatric heart surgery in Australia, in the case of Brendan Waddington.

Miss Elaine Orr

1967, Matron and Nurse Advocate.

Miss Elaine Orr was headhunted from the orthopaedic section at Frankston Hospital to be appointed Matron in 1969, in an extraordinarily difficult period in which almost every aspect of the nursing profession was changing. There were shortages of staff and much questioning of the traditional ways. She gained a reputation as a strong negotiator, intelligent and articulate who used her strong leadership to advocate for the modernisation of the nursing sector and equal rights of trainees.

Dr Keys Smith

1970, Orthopaedics, Disability and Vocational Training Pioneer.

Dr Keys Smith advocated for disability, vocational training and child rehabilitation consistently during his time at the hospital. Dr Smith thought outside the box and took a holistic approach to children’s health in dealing with the challenges of the polio epidemic, tuberculosis and osteomyelitis crisis.

During his tenure, Dr Smith helped to manage the crisis of congenital abnormalities such as spina bifida, cerebral palsy and muscular dystrophy by organising a large number of specialists, allied health workers, nurses and doctors.

To best do so, Smith shut down the Orthopaedic centre in Frankston and re-established a complete multi-disciplinary treatment centre for children with disabilities. The Handicapped Children’s Centre was established in 1970 and was the first of its kind in Australia. The centre’s services included the assessment of inpatients and outpatients, consultant visits to schools and preschools and focused on the dignity, rights and integration of the child into family and social life.

Professor Ruth Bishop AC

1973, Virologist.

Professor Ruth Bishop is one of the most famed virologists of The Royal Children’s Hospital. In the lead up to Ruth’s landmark discovery of the deadly rotavirus, approximately 10,000 Australian children were being hospitalised with the disease every year. In most cases, doctors didn’t know what was causing the acute gastroenteritis. Prof Bishop dedicated decades to searching for the virus responsible for the fatal illness.

In 1973, after years of painstaking research, Prof Bishop caught the first glimpse of the rotavirus cells: it was the most exciting and captivating cell she had ever seen. So captivating, in fact, that the circular particle shape is now immortalised in a silver necklace gifted to her from colleagues who were part of the landmark discovery of the virus. The vaccination – RV3 – is another legacy of Ruth’s pivotal research. Using a different strain of rotavirus which was discovered in 1975, it is a discovery that has revolutionised children’s ability to live healthier happier lives.

Professor Frank Oberklaid AM

1980, Pioneered Casualty Department and Emergency Services.

Professor Frank Oberklaid was one of the first Paediatricians in Australia to recognise a problem with the morbidity rates in children. This resulted in him founding the ambulatory paediatric services, the first of its kind in the country. Prof Oberklaid was met with many challenges along the way with his ideas being questioned and misunderstood. Initially he found it difficult to establish and reinvent the casualty department, which was unreceptive to his vision. The standing opinion was that The Royal Children’s Hospital was a place for the sickest of children to be brought, and the idea of going into the community was confusing and daunting.

Prof Oberklaid continued to develop the ambulatory and community services, achieving excellence through his community minded programs. In 1982 the department, under his leadership, began an outreach program to support communities in suburbs near the hospital which were characterised by diverse ethnic backgrounds, low socio-economic status and high-rise housing. These programs facilitated community maternal and child health centres, kindergartens, day care centres and community groups. His work was crucial in increasing accessibility to healthcare.

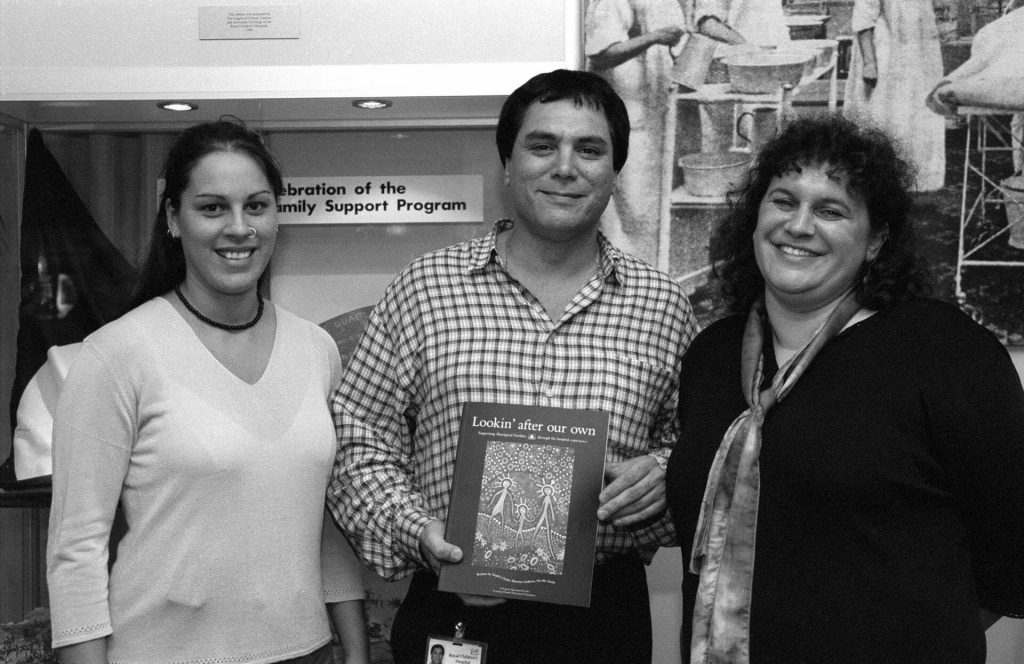

Neville Austin

1995, Indigenous Liaison Officer and Researcher.

Neville Austin, was the fourth Indigenous Liaison Officer at The Royal Children’s Hospital, employed after a 10-week student placement at the hospital. Neville achieved excellence at the hospital despite his own journey, being taken from his mother without consent as a child.

Neville was key in securing a large research grant from Vic Health, The Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, resulting in the publication Looking after our Own – Supporting Aboriginal families through the hospital experience. This ground-breaking publication set out a clear historical background to the barriers of access to the hospital for Aboriginal and First Nations people. This served as a blueprint to pave the way for other Koori Liaison Officers and help transform the way hospital services were offered to Aboriginal families across Victoria and around the country.